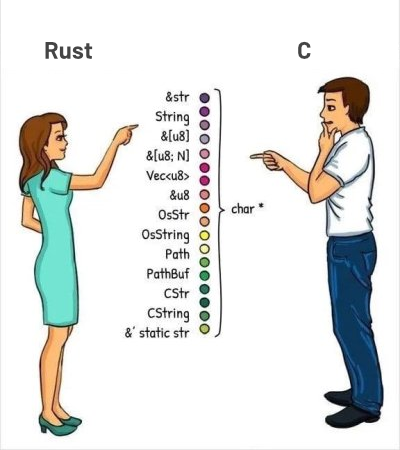

Without any ::prelude and some void* arguments.

Maybe you have thoughts about it.

The URL is just a sample of “why” but not “because”.

I have my own preference but will keep it inside my mind to not burn a tornado that will erase me from the matrix of the world.

P.S.: I think C is faster, more powerful, and more elegant. I like it more than Rust.

Rust’s 1.0 release (i.e. the date on which the language received any sort of stability guarantee) was in 2015, and this article was written in 2019. Measuring the pace of feature development of a four-year-old language by its release notes, and comparing against a 50-year-old language by counting bullet points in Wikipedia articles, is absolutely ridiculous.

Yes, younger languages adopt features more quickly, and Rust was stabilized in a “minimal viable product” state, with many planned features not yet ready for stabilization. So of course the pace of new features in Rust is high compared to older languages. But Wikipedia articles are in no way comparable to release notes as a measure of feature adoption.

I think C is faster, more powerful, and more elegant.

“More elegant” is a matter of opinion. But “faster” and “more powerful” should be measurable in some way. I’m not aware of any evidence that C is “faster” than Rust, and in fact this would be extremely surprising since they can both be optimized with LLVM, and several of the features Rust has that C doesn’t, such as generics and ubiquitous strict aliasing, tend to improve performance.

“Powerful” can mean many things, but the most useful meaning I’ve encountered is essentially “flexibility of application” : that is, a more powerful language can be used in more niches, such as obscure embedded hardware platforms. It’s really hard to compete with C in this regard, but that’s largely a matter of momentum and historical lock-in: hardware vendors support C because it’s currently the lowest common denominator for all hardware and software. There’s nothing about Rust the language that makes it inappropriate for hardware vendors to support at a low level. Additionally, GCC is probably the toolchain with the broadest hardware support (even hardware vendors that use a bespoke compiler often do so by forking GCC), and Rust currently has two projects (mrustc and gccrs) working to provide a way to use GCC with Rust. So even the advantage C has in terms of hardware support is narrowing.

But note that there are also niches for which C is widely considered less appropriate than Rust! The most obvious example is probably use in a front-end web application. Yes, C should in theory be usable on the front-end using emscripten, but Rust has had decent support for compiling to WebAssembly almost as long as it’s been stabilized.

One of the bullet points for C++ is the increase of the version number in the version header file. Wow much feature.

deleted by creator

I very much understand thinking that Rust has too much hype, but the differences between C and Rust are so fundamental that “switching between” them just to “keep your interest fresh” seems ill-advised to me. To be honest, your statements about both C and Rust so far seem pretty superficial; have you actually used Rust for anything nontrivial?

C syntax is simple, yes, but C semantics are not; there have been numerous attempts to quantify what percentage of C and C++ software bugs and/or security vulnerabilities are due to the lack of memory safety in these languages, and although the results have varied widely, the most conservative estimate (this blog post about curl; see the section “C is unsafe and always will be”) ended up with an estimate of 40%, or 50% if you only count critical bugs. If I recall correctly, Microsoft did a similar study on one of their projects and declared a rate closer to 70%.

This means that the choice of language is not just about personal preference. Bugs aren’t just extra work for software developers; they affect all users of software, which means they affect pretty much everyone. And, crucially, they’re not just annoyances; cyberattacks of various kinds are extremely prevalent and can have a huge impact on people. So if 50% or more of critical software vulnerabilities are due to the choice of language, then that is a very good reason to pick a safer language.

Rust is not the only choice for memory-safe languages. If you like the simplicity of C, you should definitely learn Go (it’s explicitly designed to be as simple as possible to learn). But I would also strongly recommend looking into Zig, which hews much closer to C than Rust does; in fact, it has probably the best interoperability with C of any modern language.

C syntax is simple, yes, but C semantics are not; there have been numerous attempts to quantify what percentage of C and C++ software bugs and/or security vulnerabilities are due to the lack of memory safety in these languages, and (…)

…and the bulk of these attempts don’t even consider onboarding basic static analysis tools to projects.

I think this comparison is disingenuous. Rust has static code analysis checks built into the compiler, while C compilers don’t. Yet, you can still add static code analysis checks to projects, and from my experience they do a pretty good job flagging everything ranging from Critical double-frees to newlines showing up where they shouldn’t. How come these tools are kept out of the equation?

I’m not familiar with C tooling, but I have done multiple projects in C++ (in a professionnel environnement) and AFAIK the tooling is the same. Tooling to C++ is a nightmare, and that’s and understatement. Most of the difficulty is self inflicted like not using cmake/meson but a custom build system, relying on system library instead of using Conan or vcpkg, not using smart-pointers,… but adding basically anything (LSP, code coverage, a new dependency, clang-format, clang-tidy, …) is horrible in those environments. And if you compare the quality of those tools to the one of other language, they are not even close. For exemple the lint given by clang-tidy to the one of Rust clippy.

If it took no more than an hour to add any of those tools to a legacy C project, then yes it would be disingenuous to not compare C + tooling with Rust, but unfortunately it’s not.

You are making an extreme assumption, and it also sounds like you’ve misread what I wrote. The “attempts” I’m talking about are studies (formal and informal) to measure the root causes of bugs, not the C or C++ projects themselves.

I cited one specific measurement, Daniel Stenberg’s analysis of the Curl codebase. Here’s a separate post about the testing and static analysis used for Curl.

Here’s a post with a list of other studies. The projects analyzed are:

- Android (both the full codebase and the Bluetooth & media components)

- iOS & MacOS

- Chrome

- Microsoft (this is probably the most commonly cited one)

- Firefox

- Ubuntu Linux

Do you really think that Google, Apple, Microsoft, Mozilla, and the Ubuntu project “don’t even consider onboarding basic static analysis tools” in their C and C++ projects?

If you’re curious about the specifics of how errors slip through anyway, here’s a talk from CppCon 2017 about how Facebook, despite copious investment into static analysis, still had “curiously recurring” C++ errors. It’s long, but I think it’s worthwhile; the most interesting part to me, though, starts around 29:40, where he asks an audience of C++ users whether some specific code compiles, and only about 10% of them get the right answer, one of whom is an editor of the C++ standard.

You are making an extreme assumption, and it also sounds like you’ve misread what I wrote. The “attempts” I’m talking about are studies (formal and informal) to measure the root causes of bugs, not the C or C++ projects themselves.

I think you’re talking past the point I’ve made.

The point I’ve made is that the bulk of these attempts don’t even consider onboarding basic static analysis tools for projects. Do you agree?

If you read the post of other studies you’ve quoted, you’d be aware that some of them quite literally report results of onboarding a single static analysis tool to C or C++ projects. The very first study in your list is quite literally the results of onboarding projects to Hardware-assisted AddressSanitizer, after acknowledging that they haven’t onboarded AddressSanitizer due to performance reasons. The second study in your list reports results of enabling LLVM’s bound sanitizer.

Yet, your personal claim over “the lack of memory safety” in languages like C or C++ is unexplainably based on failing to follow very basic and simple steps like onboarding any static analysis tool, which is trivial to do. Yet, your assertion doesn’t cover that simple step. Why is that?

Again, I think this comparison is disingenuous. You take zero effort to address whole family of errors and then proceed to claim that whole family of errors are not addressed, even though nowadays there’s a myriad of ways to tackle those. That doesn’t sound like a honest comparison to me.

You’re misunderstanding the posts you’re explaining. Sanitizers, including ASan, HWASan, and bound sanitizer, are not “static analysis tools”. They are runtime tools, which is why they have a performance impact. They’re not intended to be deployed as part of a final executable.

I don’t know how you can read this sentence and interpret it to mean that they “haven’t onboarded AddressSanitizer”:

In previous years our memory bug detection efforts were focused on Address Sanitizer (ASan).

Safety. Yes, Rust is more safe. I don’t really care.

I think this is honestly the crux of Drew’s argument.

If a compiler is to prove safety of a program in a language with low level memory management, then there is a lot of inherent complexity. Drew doesn’t like complexity, therefore Drew doesn’t like safety.

All his other arguments have some meat, though they’re debatable. This one statement is the most surprising and probably the only unacceptable stance in that entire article. Rust is just starting to be more widely used - and that success can be attributed to how much people and companies are fed up with bugs caused by unsupervised manual memory management.

C didn’t have that sort of machine supervision for safety - but then again, computers simply weren’t powerful enough to do the safety analysis back when C was created. Retrofitting an analyzer isn’t possible without changing the language completely. But today the situation is different. We have vastly more powerful computers and static safety analysis isn’t a limiting factor for newer languages. Insisting that unsafe programming is acceptable is a very regressive stance. Look for a safety paradigm with less cognitive overhead to the programmer? That’s worthwhile. But safety is an absolute necessity. If decades of programming has taught us anything, it’s that even the most knowledgeable coders can make mistakes with disastrous consequences due to momentary lapses in judgment. There’s no justification in not using the computing power at our disposal to catch such mistakes when they happen.

Why are you posting a 5 year old blog post? Me thinks it’s to stir the pot.

C is many things, but elegant really isn’t one of them.

C has always been part of the “worse is better”/New Jersey school of thinking. The ultimate goal is simplicity. Particularly simplicity of language implementation, even if that makes programs written in that language more complex or error prone. It’s historically been a very successful approach.

Rust, on the other hand, is part of “The Right Thing”/MIT approach. Simplicity is good, but it’s more important to be correct and complete even if it complicates things a bit.

I don’t really think of void* and ubiquitous nulls, for example, as the hallmark of elegance, but as pretty simple, kludgey solutions.

Rust, on the other hand, brings a lot of really elegant solutions from ML- family languages to a systems language. So you get algebraic data types, pattern matching, non-nullable references by default, closures, typeclasses, expression-oriented syntax, etc.

C has always been (…)

I think you tried too hard to see patterns where there are none.

It’s way simpler than what you tried to make it out to be: C was one of the very first programming languages put together. It’s authors rushed to get a working compiler while using it to develop an operating system. In the 70s you did not had the benefit of leveraging half a century of UX, DX, or any X at all. The only X that was a part of the equation was the developers’ own personal experience.

Once C was made a reality, it stuck. Due to the importance of preserving backward compatibility, it stays mostly the same.

Rust was different. Rust was created after the world piled up science, technology, experience, and craftsmanship for half a century. Their authors had the benefit of a clean slate approach and insight onto what worked and didn’t worked before. They had the advantage of having a wealth of knowledge and insight being formed already before they started.

That’s it.

It’s really not just that Rust is new and C is old. Compare Rust with Go, for example. Go is a fairly modern example of a ‘worse is better’ language.

Back in 1970s when C was invented, Lisp had been around for over a decade. C came out the same year as smalltalk, a year before ML, and 3 years before Scheme.

Rust is a very modern language, yes. There’s no way we could have had it in the 70s; many of its language features hadn’t been invented yet. But it very much depends on MIT style research languages for its basis.

Interesting how Richard Gabriel framed it as New Jersey (Bell Labs) vs MIT.

This is an old post and a lot has changed since then. Many of the points in that article are no longer true. Drew himself started a language - hare, for which he is considering Rust style borrow checker to ensure safety. It’s a bit wrong to bash anything based on a half a decade old opinion.

Oh another Rust vs C discussion.

I bet the comparisons totally won’t be controversial on both sides at all. That never happens.

Did you try to add an image and remove the URL to the article im the process?

This is an opinion and conclusion I completely expected to see from Drew. He’s carrying the torch for the old guard but damn if it’s not an uphill battle these days.

deleted by creator

If you have references explain why and how that it’s easier to port C to a new architecture by creating a new compiler from scratch than to either create a backend for llvm (and soon gcc) or to create a minimal wasm executor (like what zig is doing) to this new architecture I’m interested. And of course I talking about new architectures because it’s much easier to recreate something that as already be done before.

deleted by creator